Stories Before 1850. 0199: William Darton (?), The Rational Exhibition

| Author: |

Darton, William, Snr. [?] |

| Title: |

The Rational Exhibition. With copper-plates |

| Cat. Number: |

0199 |

| Date: |

1824 |

| 1st Edition: |

1800 |

| Pub. Place: |

London |

| Publisher: |

Harvey and Darton. Gracechurch Street, and William Darton, Holborn Hill |

| Price: |

1s |

| Pages: |

1 vol., 60pp. |

| Size: |

16.5 x 10 cm |

| Illustrations: |

Engraved frontispiece plus 22 further plates |

| Note: |

Book-list on outside back cover |

Images of all pages of this book

Introductory essay

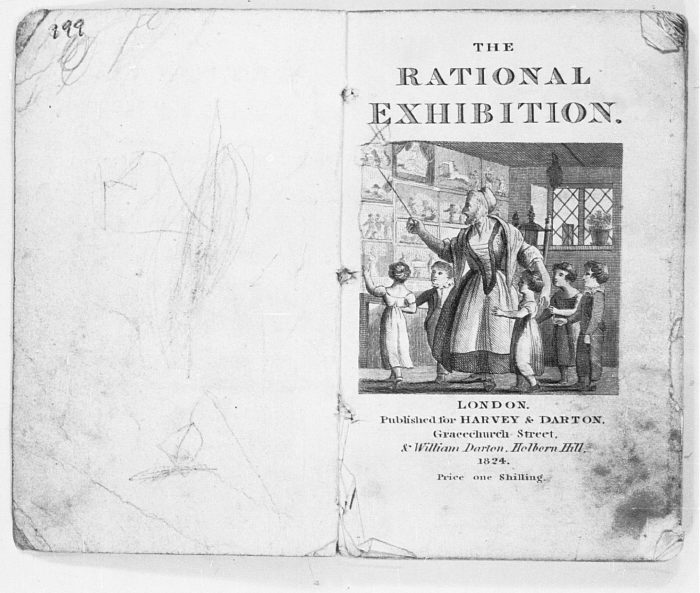

The conceit which underlies The Rational Exhibition is that an old woman of the narrator's acquaintance had papered one wall of her abode with various prints and pages of text (pictured, but not wholly as the text describes it, in the frontispiece). These papers had belonged to her grandchildren, and they had been papered to the wall so that the grandmother could use them as a prop for the education of other children. Representations of the prints and texts, accompanied by the grandmother's explanations, are what follow over the next sixty pages. This scheme is reminiscent of Sarah Trimmer's various series of prints for the teaching of scriptural or secular history (see 0453-0456 and 1145-1152). These were available for purchase either in book form, or 'sewed in Marble Paper for the pocket, or 'pasted on boards for hanging up in nurseries'. Trimmer began her scheme in 1785. They remained in print well into the nineteenth century.

For its part, The Rational Exhibition had first appeared in 1800, also published by Darton and Harvey. By the time of this new edition of 1824, the prints had been re-engraved (the final one is dated 1824 - p.60), the various episodes had been re-ordered, and the price had gone down - from 15d. to one shilling (a circumstance explained by a fly-sheet note in the 1800 edition which laments that paper had just increased in price by thirty per cent). Most of the episodes contained in the first edition survived in the 1824 re-publication. Only a duck-eating-frog and a description of a barber's shop, along with an account of how various nations have regarded beards, are omitted. What remains is a real hotch-potch. There are anecdotes, news stories (mostly dated 1799 or 1800), snippets of natural history, short poems, Biblical histories, accounts of remarkable people to be found on the streets of London, the almost obligatory description of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, and an extract from Thomas Day's Sandford and Merton. Some of the anecdotes teach simple moral lessons - the importance of obeying one's parents (for they only have your best interests at heart), the obligation to be kind to animals (for the often help you in return), and the folly of reading in bed by candle-light (one can set one's hair on fire). But the lesson is usually subordinate to the amusement value of the anecdote. Above all, the chief attractions remain the copper-plate prints, which are high quality and provide the raison d'tre for the text.

These prints, and the text which accompanies them, were probably by William Darton Snr. himself. The attribution comes from the bibliography of a fellow Quaker, Joseph Smith, whose A Descriptive Catalogue of Friends' Books (1867) lists Darton's own contributions to his children's books list.