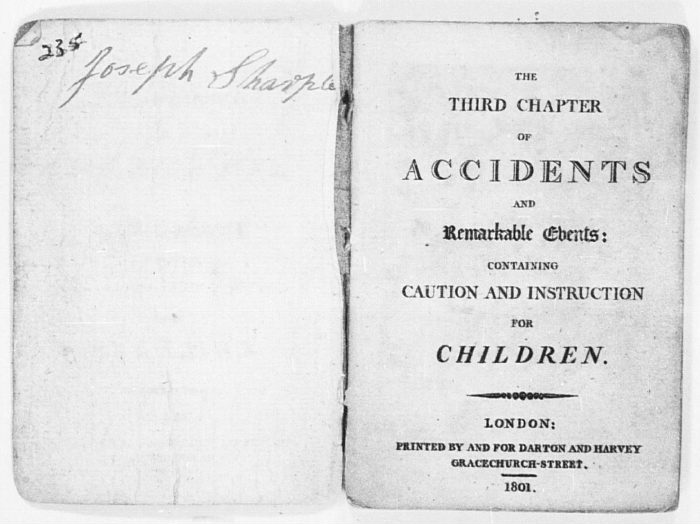

Stories Before 1850. 0235: William Darton Snr.(?), The Third Chapter of Accidents and Remarkable Events

| Author: |

Darton, William, Snr. [?] |

| Title: |

The third Chapter of accidents and remarkable events: containing caution and instruction for children |

| Cat. Number: |

0235 |

| Date: |

1801 |

| 1st Edition: |

1801 |

| Pub. Place: |

London |

| Publisher: |

Darton and Harvey |

| Price: |

Unknown |

| Pages: |

1 vol., 50pp. |

| Size: |

12 x 7.5 cm |

| Illustrations: |

15 copper-engravings |

| Note: |

Inscription on fly-leaf: 'Joseph Sharple[?]' |

Images of all pages of this book

Introductory essay

Three separate 'Chapters of Accidents' were published by Darton and Harvey, of which the Hockliffe Collection contains only the third. All were published in 1801 (although oddly, one of the full-page engravings in this third chapter bears the date 15 May 1802). It seems likely that the work was actually written and illustrated by its publisher, William Darton Snr. This attribution is made in a list supplied by T. Gates Darton for an article on the Darton firm in The Bookseller of 2 September 1873. Darton had trained as an engraver before setting up his publishing business in 1787.

Each of the three parts of Darton's work is composed of descriptions of a succession of accidents. They were probably gathered from newspapers and books of travel or history. Some affect children, and take the form of rudimentary cautionary tales. They warn young readers against playing blind man's buff in a room with a fire (which leads to a dress being set ablaze), for example, or reaching for a sugar pot kept on a high shelf (which results in a boy's hand being caught in a rat-trap). Others deal with accidents which might happen to anyone. A section in part two deals with the etiquette of walking in London, for instance. It was formerly the custom to 'take the wall' from one's inferiors, we are told (that is to say, to attempt to walk nearer the wall-side of the pavement than any social inferior). But such a practice is dangerous, the text counsels, for if one endeavours to pass anyone one meets on the left-hand side, then walking into people, and especially porters bearing loads, will be avoided. Still other sections deal with accidents which early nineteenth century British readers were unlikely to bring upon themselves - encounters with a bear, a lion or an elephant for instance. This third chapter includes the most dramatic accidents of all, including a woman frightening off a Bengal tiger with her umbrella, a lion decapitating a man, a man falling from a balloon and a horse and rider plunging off a bridge.

Sarah Trimmer thought the engravings the chief merit of the book when she reviewed it in her Guardian of Education (1802). The text, she though, was 'an odd sort of composition, in which natural history and stories of accidents are jumbled together with no regard to regularity or arrangement'. With a little judicious cutting by the parent, she felt, the book could be useful.